A Stubborn Grandpa

My grandpa had a hole in his nose.

It was a fairly little hole, dark black, on the left side. You couldn’t miss it.

The doctor dug the skin cancer out of Thomas Cecil’s nose and told him to come back and get the hole filled. Who wouldn’t get a hole in their nose filled?

Well now, that would be my grandpa.

He refused to go back in. He didn’t like doctors. He wasn’t quite sure he trusted them and their quackery to begin with and he sure as heck didn’t like their bills.

When he didn’t return, the doctor called and begged him to come back. Offered to fill the hole for free. My grandpa said, “Hell no.”

So the hole in his nose stayed right where it was. To understand his decision, you might need to understand him.

My grandpa grew up poor on a farm in Arkansas. He was one of eleven. There were three wives who all died before his father. After finishing an eighth grade education, he continued the back breaking work on the farm, then he and his brothers took off for Los Angeles and built solid, strong houses.

His childhood was so difficult that he changed his name from Cecil Thomas to Thomas Cecil on the way to Los Angeles. Shed the name, shed the pain.

Thomas Cecil married my nana, Mary Kathleen, and couldn’t stay in one place. By the time my mother was seventeen years old, she’d moved eighteen times. He would buy a house, flip it, and move on.

In the construction business it was boom or bust for them. Sometimes my grandpa made a lot of money building homes. The first thing he did with that pile of cash? He bought an expensive, flashy car.

My mother hated the attention they received riding in those sleek cars. Hated when people turned to point at their car. Hated when he flashed his wealth. My grandpa loved those cars. He wasn’t poor anymore. He wasn’t the farmer’s son with an eighth grade education feeding pigs at dawn and milking cows. He was someone.

But a couple of times, at least, my grandpa went bust. He built homes, the market crashed, and he was left with the homes and a financial disaster. They would be wiped out and the flashy car would go.

He was again that poor, desperate boy on the farm, scratching out a living.

To complicate it further, my grandpa suffered from depression.

Genetics? Maybe. A chemical imbalance? Maybe. His mother died when he was four. Lost in a crush of kids, no mother, maybe it started then. Maybe it started on the farm, poverty hanging like a scythe over the property.

My mother remembered her father’s depression. Remembered how down he would get, how the blackness would cover him.

And yet.

He still worked. Still built homes. Still provided. Still did the best he could do. He worked despite the emotional storm in his head, the thunder and lightning crashing in on him, the claws that were pulling him down.

And that hole in his nose he refused to fix? That tells you a lot about his personality. He didn’t care what anyone thought of him or his nose.

He didn’t like doctors, so he wasn’t going back and that was that.

At the end of his life, cancer eating him alive from decades of smoking, my mother practically had to drag that stubborn, sick man to the hospital. By then it was too late, cancer’s tentacles everywhere. My nana had been dead for years by then, he was terribly lonely, and ready to go.

Thomas Cecil dearly loved his family, his wife, his daughter, and his grandkids. He worked hard, despite the depression that wanted to shut him down and out. He dug his way out of poverty. He saved and sent his daughter to college, something he never had.

And when he lost it all, he went back out and started over, again and again.

My grandpa had a hole in his nose. It is only one of many, many important memories and life lessons I have from him.

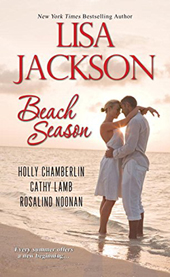

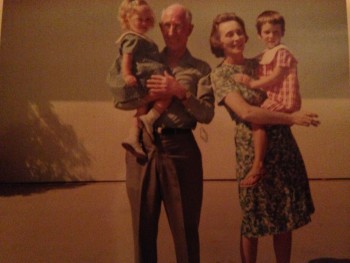

*** Photo of my grandpa, nana, oldest sister and me.