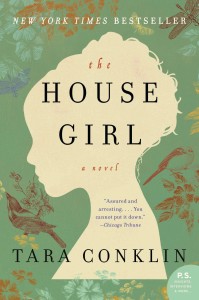

Author to Author Interview: Tara Conklin

Cathy Lamb: I read every night to battle my looming insomnia, so I go through a lot of books. House Girl was one of my favorites. My only complaint was that it kept me up so very late.

Your novel combined history and art, two of my favorite topics to read about. I also thought the way you moved back and forth from a slave plantation in Virginia in 1852 to modern times in New York provided a compelling structure.

Tell everyone about the plot. What was the trigger for the story?

Tara Conklin: The original spark for The House Girl came from the words “slave doctor” that appeared in a biography I was reading. Those words made me stop. I wondered what would drive someone to occupy a role that to me seemed inherently conflicted: to dedicate your life to healing and yet your patients were destined only for more and graver harm.

I began to write a story about a slave doctor, a man I named Caleb Harper, and two women appeared in his story: Dorothea Rounds, a young white woman active on the Underground Railroad and Josephine Bell, a young house slave and artist on a Virginia tobacco farm. I wanted to know more about these women and so I began writing their stories, and then I was off.

Josephine felt real to me. I was so attached to that character that during certain scenes I actually felt myself cringing. Did she come completely from your imagination or was there a slave you read about who was your inspiration?

Josephine is purely herself – she isn’t based on any actual historical figure. In developing her character, however, two women were very important. The first was Mary Bell, an early 20th century African-American artist who worked as a house maid for a wealthy Boston family.

She drew pictures of elaborately dressed, wealthy white and light-skinned black women using the only materials available to her – crayon, pencil and the tissue paper used to make dress patterns. The drawings are odd – the women all wear pained, tense smiles – and I remember thinking when I first saw them 20 years ago: what would Mary Bell have drawn if she chose subjects close to her heart? If she drew the people and things that she loved? This question determined the subject of Josephine’s art: the people and places that she loved.

The other woman who was important is Elizabeth Mumbet Freeman. She lived in my home town of Stockbridge, MA, and was enslaved in Massachusetts before and during the Revolutionary War. She overheard her master talking about the Declaration of Independence and wondered why its promise of freedom for all did not apply to her. In 1781, she sued for her freedom in a Massachusetts court and won, ushering in a number of ‘freedom suits’ that eventually resulted in the abolishment of slavery in the state. Her strength of purpose helped me understand Josephine Bell.

What about Lina? She’s an attorney. You are, too. Is there some of you in Lina?

Readers often ask if Lina is auto-biographical and the answer is an emphatic no. I went to law school after working in non-profits for five years, then practiced law for seven, and I enjoyed being a lawyer for about six of those. Lina goes straight from college to law school and her reasons for doing so are based largely on stability and wanting a life different than her artist father’s.

The details of Lina’s world, however, are based on my time at a big corporate firm and some of her experiences (for example, the opening scene where a partner tells her that a case has recently settled) are drawn from my professional experiences.

It was heartbreaking to read about the lives of slaves in your book. It always is. Was researching slavery difficult, knowing how much they suffered? Were there any other stories about slavery that particularly stuck with you?

To research the historical sections, I read history books, slave narratives and any other first person accounts I could get my hands on from the time period. The research was indeed difficult, but it was also inspiring to read about the courage and strength of those who managed to escape from slavery (virtually all 19th century slave narratives are written by those who escaped.)

At a certain point, however, I needed to stop researching. The horror of slavery became overwhelming – the individual losses, the injustice, the waste. I had to pull back and focus not on slavery as an institution but on Josephine Bell: one woman, one story. I remember distinctly reading Solomon Northrup’s narrative (now the basis for the film 12 Years a Slave) and wanting to know more about the practice, common in the 1850s, of capturing free blacks in the North and selling them into slavery in the South.

I explore this in the book through the character of Benjamin Rust, a slave catcher. The slave narrative Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet Jacobs also stayed with me. After fleeing her abusive master, Jacobs spent nearly seven years hidden in the attic crawl space in her grandmother’s house. The situation evokes Anne Frank’s attic hideaway but Jacobs’ story is far less well-known. Jacobs offers a detailed account of the particular suffering that women endured under slavery: routine sexual abuse at the hands of white slave owners, mistreatment by white mistresses, separation from children and partners.

The lives of slaves, particularly the women, are just devastating to think about and I’m glad you were so rawly honest in your re – telling of it.

One part of The House girl I was especially intrigued with was the art that Josephine painted, and yet Lu Ann, her slave owner, received the credit and the money. Which brought the story around to reparations for descendants of slaves. Can you elaborate on your thought processes as you included that piece in The House Girl?

Part of the art angle came from Josephine’s character herself. I knew early on that Josephine had this creative spark, an artist’s sensibility and need to create – this was the key to her character and I wondered how that would have played out within the context of her relationship with Lu Anne. As I researched the antebellum period, I was also continually struck by the overwhelming waste – waste of life, intelligence talent, love, family. And what might have come from all the hearts and minds that were thrown away in the cotton, sugar and tobacco fields? Josephine’s art was just one small way of answering that question.

On a more personal note, tell us about yourself. Where do you live, with who? Do you have a garden, pets, hobbies, interests?

I have three kids (ages 7, 6 and 18 mos) so they are my hobby. I live with them and my husband Nick in Seattle. We have no pets and I am an atrocious gardener. In the rare moments when I’m not looking after the kids or writing, I run, practice yoga (badly) and occasionally try to cook something adventurous.

Living in Seattle, we’re surrounded by such physical beauty and we try to take advantage of it whenever we can on the weekends – hiking, skiing, camping and swimming in the summers.

You have a BA in history from Yale, a JD From NY University and a Master of Law and Diplomacy from the Fletcher School at Tufts. You were a litigator in New York and London. And now you’re a writer. Was this the plan? Or is writing a new ambition?

Contrary to what my diverse education might indicate, I’ve always wanted to be a writer; I just never thought I could make a living at it (and I’m still not sure!) I’ve been a voracious reader since earliest childhood and I think wanting to write flows pretty naturally from a love of books. I began keeping a journal at about age 9 or 10 and throughout my life I’ve been a scribbler of stories. In the back of my mind, I always had this vision of me in retirement – obligation-free days and me at my laptop, writing. After the birth of my first child, something shifted in me and I realized that I couldn’t wait that long – so I decided to retire early.

What does a typical day look like for you? When do you write? Do you set daily writing goals? Are you up until two in the morning all the time, like me?

When I’m traveling, I don’t have much of a writing routine, unfortunately. I’ve been finding it very difficult to promote The House Girl while working on another book. When I’m not traveling, my routine is fairly set: as soon as my babysitter arrives at 9:00 am to watch my youngest (my older two catch the school bus at 7:45), I head to my favorite coffee shop with my laptop where I drink copious amounts of coffee and type as fast as I can until the babysitter leaves at 1:00. I then often start working again after the kids are in bed, around 8 pm. I don’t set myself goals – I just write for as much time as I’ve got.

I, too, write in coffee shops. Every day. One might call me a Starbucks fanatic, but I digress…Name three favorite writers, one from the 1800s, one from the 1900s and one from modern times.

1800s: Leo Tolstoy; 1900s: Virginia Woolf; modern: Jennifer Egan.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on a novel about three adult sisters and how they come to terms with the death of their brother. It’s a contemporary family portrait, focusing on the sibling relationships and how they change and shift over time.

Oh, my. What a coincidence. I have two sisters and a brother. Relationships do shift, don’t they? I’ll look forward to the next book. Thanks for your time, Tara!

I love this interview. I have not yet read THE HOUSE GIRL; but I plan to now! Thanks to both of you for sharing so much of yourselves.

1I am hooked on “the House Girl” just by reading your conversation with the author….It will be on my list when I finish typing.

2